Fine Art Appraisals

USPAP and IRS Compliant Art Appraisals

We are educated and equipped to conduct appraisals for a variety of purposes including:

Insurance – Estates – Gift Tax – Art as Collateral – Informational – Damage / Loss – Possibility of Sale

Our firm specializes in the art of appraisals. Veritas appraisal reports are written with meticulous detail and quality. Reports are written according to the standards set forth by the American Society of Appraisers (ASA), Appraisers Association of America (AAA), the IRS, and also in conformity with the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP). Before conducting appraisals, we ensure that the client’s needs are clarified so that the scope of work is properly laid out.

Art Advisory Services

We have extensive experience navigating the many services that fall under the art advisory umbrella. Our services include, but are not limited to:

Collections Management

This involves the physical care and maintenance of your collection. This includes, but is not limited to: inventory, storage, handling, cataloguing, framing, conservation advice, and advice on installation. Veritas actively works with both private collectors and institutions in this capacity. We also have extensive experience with various sophisticated collections management software, including Cloud-based systems.

Conservation / Restoration Advice

Often times a work of art suffers from faulty or outdated restoration methods. This can greatly distort the interpretation of the piece and be a detriment to its historical and monetary value. Veritas is connected with the most reputable conservators in the field and has experience in preparing condition reports for museum and private collections. We can guide you through the process of having a collection or simply one piece of art restored or conserved.

Authentication Services

Our team is well versed in art historical research and properly connected with a vast network of museum professionals, scholars, and scientists to facilitate the proper authentication of a work of art. It is important to know that locating the appropriate authority for a particular artist or genre is imperative in art authentication. Many times finding these authorities is very time consuming and difficult without the proper connections. We have helped many clients find and work through the art world’s accepted channels to authenticate works of art.

Restitution of Nazi Looted Art / Provenance Research

We are proud to work with clients on the issue of restituting artwork stolen from families during the Nazi occupation. This involves a wide variety of research skills and art historical knowledge as well as maintaining the right international and domestic connections to achieve our clients’ restitution and research goals. Provenance research is a major component of restitution work. Our passionate approach to this is focusing on combining our academic background with practical experience in the field. For inquiries regarding this service please contact Carrie Laverick at cbaker@veritasartappraisals.com.

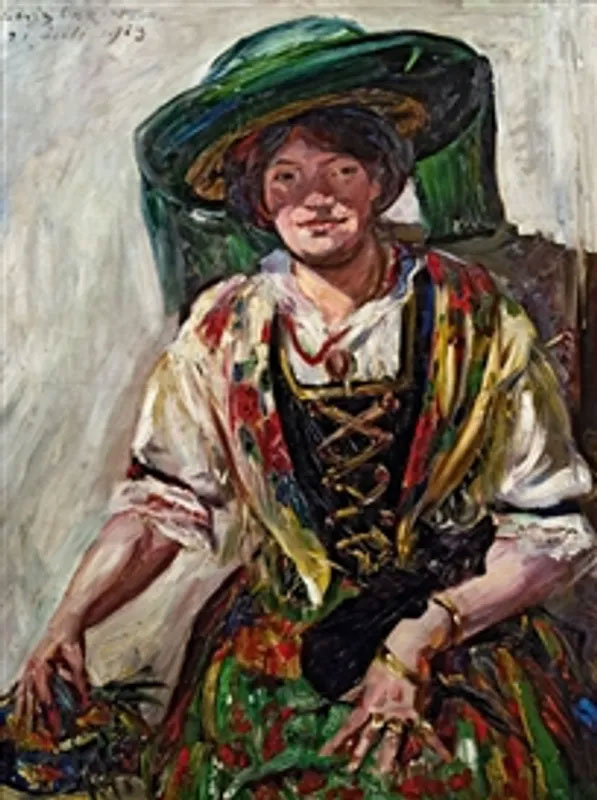

IMAGE: “Tyrolean Woman with Cat” Lovis Corinth (German 1858-1925) Veritas is currently working with a family to restitute this important work along with other pieces that belonged to their Grandparents, who both perished at Auschwitz in 1944. The piece is also listed on the Monuments Men Foundation’s “Most Wanted” list at http://monumentsmenfoundation.org.